Imikotoba (taboo words)

August 24, 2011

Imikotoba (忌み言葉), or taboo words, are words that are avoided because they are believed to bring bad luck. The term can also mean the euphemism or replacement that is used instead of them (either an alternate pronunciation or a substitution word).

Some of these taboos are related to specific moments and rituals, while others are spread among the general population and condition the daily use of the language.

Those of you who understand some Japanese know how there are two series of numbers, one being based on Chinese reading or on-yomi (ichi, ni, san…) and the other on Japanese reading or kun-yomi (hitotsu, futatsu, mittsu…). Now, the Chinese reading for “4” is shi, but Japanese people tend to avoid this pronunciation and substitute it with the kun-yomi for “4” which is yon; this use, so common to be the rule with many counters, is due to the fact that shi is also the pronunciation of the character 死, which means “death”.

Another example: the most common word for pear is nashi 梨. Nashi, however, is also the pronunciation of 無し, which means “none.” To avoid the hazards of this association, the word ari-no-mi / 有りの実 (lit. “the fruit of abundance”) can also be used to refer to a pear.

Other substitutions are atarime (for dried squid, surume) and etekō (for monkey, saru, whose homophone means “depart” and is used as a euphemism for death).

Other words are to be avoided especially to preserve the purity of Shinto rituals. The Engi Shiki lists taboo words associated with the saigū (Chief Priestess) of the Grand Shrine of Ise and their replacements:

1. Inner seven (related to Buddhism)

buddha(s): nakago (“middle child,” i.e. seated in the center of the worship hall)

sutra: somekami (“dyed paper;” originally printed on yellow paper)

pagoda: araraki (Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese-based word, also pronounced araragi)

temple: kawarafuki (“tiled,” as in “tiled roof,” also pronounced kawarabuki)

monk: kaminaka (“long-haired,” also pronounced kaminaga)

nun: mekaminaka (“female long-haired”)

vegetarian food/abstinence: katashiki (“one tray”).

2. Outer seven (related to non-Buddhist words)

death: naoru (to recover)

illness: yasumi (to rest)

weeping: shiotare (“shedding salt”)

blood: ase (sweat)

to strike: atsu (caress)

meat: kusahira (vegetables and mushrooms)

grave: tsuchikure (clod of earth).

3. Others

Buddhist hall: koritaki (“incense burning”)

lay Buddhist (ubasoku): tsunohasu (“notch of arrow,” also pronounced tsunohazu).

Other taboos are still avoided by ordinary people in special events such as weddings and funerals.

For example, if you have to give a speech at a weddings you should carefully avoid words such as hanareru (離れる, to separate), kiru (切る, to cut) or wakareru (別れる, to split) because they can be seen as references to divorce; for the same reason, one should not use words that repeat the same sound, such as tabitabi (たびたび, frequently) or iroiro (色々, various).

At funerals, one cannot use words that infer “something sad will happen again”, “your sould cannot rest in peace” or, again, repeated sounds. Some examples are tsuzuku (続く, to continue), ukabarenai (浮ばれない, your soul cannot rest), kaesugaesu (返す返す, repeatedly).

Also you cannot use words such as nagareru (流れる, to wash away) or kieru (消える, to disappear) when congratulating a pregnant woman, because they might sound like references to miscarriage.

There are taboo words for school tests as well: during the entrance exams season, one should avoid words that make one think to failure, such as chiru (散る, to disperse), suberu (滑る to slip over), ochiru (落ちる, to fall).

Purity and pollution

June 8, 2011

I’ve already mentioned how impurity or kegare (汚れ or 穢れ) is a major concern in Japanese religion. Even though nowadays the emphasis is placed more on mental or spiritual pollution, kegare originally had no moral meaning, rather being the reaction of natural forces that caused misfortune. Some scholars interpret it to mean the exhausting of vitality, that is to say a condition in which ke=ki (vitality) has withered (kare). It was thought to be caused by the contact with impure things such as death of humans and domestic animals, childbirth, menstruation, eating meat and sickness. Since kegare is an impediment to religious cerimonies, those who are polluted with it cannot take part to them.

A related concept is imi (忌み or 斎み), which can be translated as “mouring” or “avoidance”; it is a period in which one has to stay pure in order to celebrate ceremonies. The Taihou code (701) imposed a set of rules for the Emperor, in order to keep him protected from kegare. There were imi periods in which the ruler in which he could not: attend a funeral; see sick people; eat meat; sentence someone to death; play a musical instrument – and other supposedly impure activities.

Repulsion for impurity is anything but uncommon among cultures of the world. The concept of tittu, spread among people in southern India, is similar to kegare. Also the repulsion for shoku-e (触穢 touching impurity) are acknowledged in the Bible (e.g., Leviticus 5.2-3).

Kegare was considered contagious as if it were an infective disease: it was believed to be transmitted not only by physical contact but also by handling objects such as food, fire etc. Furthermore, it could be transmitted from person to person up to three times, as stated by Engishiki (905).

The link with childhood and menstruations is also the reason why women were considered impure (again, this fact is common in many primitive cultures, up to superstitions that survive in our civilization as well). However, women were not considered impure in ancient Japanese society: actually, they were considered closer to kami; the concept of impurity stemming from blood became stronger alongside with the exclusion of women from power and reached the top with Buddhism. In the 14th century the sutra Ketsubon-kyoo was introduced in Japan; it stated that women were so impure to deserve being tortured in hell, since they were polluting earth and rivers with their blood. This concept still survives and it’s the reason why women are prevented from taking part in some institutions such as nou theatre, sumo, the pageants of Gion festivals and some shrines and rites.

In order to restore a condition worthy of approaching the gods, one has to undergo ritual ablutions (misogi, 禊) and rites of purification called harae (祓祓) – which is the traditional pronunciation is harae, but today the word is usually pronounced harai. Purification rites are still a core part of Shinto and are performed both for special purposes, and at the beginning of all religious ceremonies. As observed by Ono Sokyou, matsuri has four such elements, including (1) purification (harai); (2) offerings (shinsen); (3) litany (norito); and (4) a communal feast (naorai); the purification must be the first step, representing the separation not only form the pollution, but also from the profane world.

Shinjuu

May 1, 2011

Yesterday, at the Far East Film Festival (Udine), I’ve seen “Villain” (悪人) by Lee Sang-il, based on the homonymous novel by Yoshida Shuichi, in which a girl falls in love with a murderer and runs away with him.

Now I am not talking about the film, but about another “crazy thing people do for love”, that is to say shinjuu or double suicide.

In common parlance, the world shinjuu (心中) is used to refer to any group suicide of persons bound by love, typically lovers, but also parents and children and whole families.

Double suicide by lovers is a popular topic in Japanese theatre, which has a whole repertory of plays (the oldest was probably “The Soga Successors” in 1683) in which two people, being their ninjou (人情, human feelings) are at odds with giri (義理, social obbligation), decide to commit suicide together, in order to meet again in afterlife. The tragic act is usually preceded by a michiyuki (道行), a small journey in which the two people evoke their happier moments and spend their last time together.

To understand this custom, we have to remember how Japanese view on suicide is far different from the western one, valuing honour of life over its lenght. This is influenced by Buddhism, which, unlike Christianity, doesn’t consider suicide as sinful. Suicide is even seen as an honourable or expected act, as in the cases of seppuku or kamikaze; actually, talking about suicide in Japanese culture might take forever, so going back to the specific issue of suicide for love, it is worth mentioning how it was influenced also by the belief, spread in Pure Land Buddhism, that the bond between husband and wife is continued into the next world (while the one with kids was supposed to last only in this world).

However, double suicide of lover was another matter, since it suggested a kind of freedom of love, which was considered anti-social in feudal Japan, so it was seen as an act of rebellion. The death of a courtesan was also a huge

economical loss for her owner. Nevertheless, such a practice was common among star crossed lovers, that were also inspired by fictional examples: the performance of “The Love Suicides at Sonezaki” by Chikamatsu (1703), based on a real story, was followed by so many cases of young people committing shinjuu, that government had to ban the performances of double suicide plays altogether in 1723.

Literally, the word “shinjuu” does not mean “suicide” but “inside the hearth” and originally meant simply any way to prove faithful love between a courtesan and her lover. It could have been a special letter of a vow or a few hairs, or a tattoo on the arm, or even to cut off a little finger. This custom became so fashionable that special boxes for keeping those items were on sale – and, as a consequence, those means of proof came to be undervalued, so that suicide was regarded to be the only trustworthy way to prove one’s true love.

The Doukyou affair

April 20, 2011

In my post about Nagaoka-kyou I mentioned the Doukyou affair – now let’s see something more on the topic.

Doukyou (道鏡, 700 – May 13, 772) was a Buddhist monk of the Hossou school. He was born in the Yuge family, in the lineage of the Mononobe clan (yes, the conservatives that had opposed the introduction of Buddhism in 538 – but a couple of centuries can change many things…) so he was known also as Yuge no Doukyou (弓削道鏡). He had been a disciple of the monk Gien and learned Sanskrit from Rouben. In addition, it was said that he acquired the spells of Esoteric Buddhism while studying in the mountains of Yamato Province.

In 761 he cured a mysterious illness of Empress Kouken, who had reigned from 749 to 758, then abdicating in favour of her cousin Emperor Junnin. The nature of their relationship was not clear, however they are often reasoned to have been lovers. At that time, Kouken was 43 years old, Doukyou was 61. The Nihon Ryoiki, written at the beginning of the ninth century, says “the priest Doukyou and the retired empress shared the same pillow”.

In the sixth month of 762, Koken became irritated with the ruling Emperor and decided to excercize her influence as a retired Empress, like her her mother, Empress Koumyou, had done. She suddenly left the detached palace at Hora and took up residence at a Buddhist temple in Nara, issuing an edict stating that “henceforth the emperor will conduct minor affairs of state, but important matters of state, including the dispensation of swards and punishments, will be handled by me”.

In 763 Doukyou was appointed Shosozu.

In 764 Fujiwara no Nakamaro plotted against the two; scholars have reasoned about the causes of his strong opposition, which are probably due not so much to an anti-Buddhist feeling, but rather to different opinions on the role of the Emperor, Koutoku favouring the Chinese model, in which the monarch had an actual power, while Nakamaro and his supporters preferred the usual practice of having the Emperor devoted to rituals and the current affairs in the hands of a related clan. Anyway, his rebellion failed, and he was executed in Lake Biwa with his wife and children.

On January 26, 765, Kouken reascended the throne with the new name of Empress Shoutoku (not to be confused with Prince Shoutoku). The same year Doukyou was appointed Daijin Zenji. In the next year he was promoted to Hō-ō (法王; king of the Dharma).

In 769 he obtained a divine proclamation from the Shinto god Hachiman at the Usa Shrine that prophesied peace in the realm if Doukyou were proclaimed Emperor. Shortly afterwards, Empress Shoutoku is said by the Shoku Nihongi to have herself received a message from Hachiman advising her to have the authenticity of the report checked. So she dispatched Wake no Kiyomaro to the Usa Shrine to find out what Hachiman’s wishes were.

Kiyomaro returned to the capital, he brought back quite a different version of the Hachiman oracle:

Ever since the founding of the Yamato state, emperors and empresses have been selected by their predecessors. But no minister has ever become emperor.

An emperor or empress must necessarily be selected from those who are in the Sun Goddess’s line of descent. A person not selected in accordance with this principle should be summarily rejected.

This report angered Doukyou, who used his influence to have an edict issued sending Kiyomaro into exile; he also had the tendons of Kiyomaro’s legs cut, and only the protection of the Fujiwara clan saved him from being killed.

The chief priest of the Usa Shrine may have been trying to ingratiate himself with Shotoku and Dokyo by passing along the first version, and the Fujiwara clan might have arranged for Kiyomaro to bring back the second. We do not know what really happened except that efforts to make Dokyo the emperor were blocked.

In the eighth month of 770 Shotoku suddenly died of smallpox, without having selected a successor. The Fujiwara managed to have Prince Shirakabe was enthroned as Emperor Kounin. Doukyou was removed from his high offices and was exiled to the province of Shimotsuke.

Wake no Kiyomaro was recalled from exile and appointed as both governor of Bizen Province and Udaijin. The following year, he had officials sent to Usa to investigate allegations of “fraudulent oracles”; in his later report, Wake no Kiyomaro stated that out of five oracles checked, two were found to be fabricated, so he had the head priest replaced by the previously disgraced one.

The introduction of Buddhism in Japan

March 28, 2011

While I am not so much into the history of Buddhism generally speaking, I am intrigued by the facts surrounding its introduction in Japan.

There are two theories on how it was introduced. The first one is based on the famous Nihon Shoki (720), the other on an early history of Yamato’s first great temple entitled “Gangouji Garan Engi Narabi ni Ruki Shizaichou” (元興寺伽藍縁起并流記資財帳?, “Origins of the Gangouji Monastery and Its Assets”), also known as Gangouji Garan Engi, compiled by an unnamed Buddhist monk in 747.

– According to the Nihon Shoki accounts, Buddhism was introduced in Japan in 552, the thirteenth year of the Kinmei reign, when King Songmyong of Paekche sent to the Japanese Emperor an envoy bearing (together with a plea for military aid against Silla) a Sakyamuni idol, two Buddhist scriptures and and a message in which Songmyong recommended the adoption of Buddhism on the grounds that this religion had greatly benefited the rulers of other lands. Emperor Kimmei, says the Nihon Shoki, “leaped for joy”, but his ministers were less jubilant: while Soga no Iname was enthousiastic, Mononobe no Okoshi was reluctant, being concered to offend the native kami, on whose benevolence depended the abundance of the harvest and the health of the state

Since the ministers were divided on the issue of the adoption, Kinmei had Soga no Iname perform Buddhist rituals experimentally. Iname turned his house into a temple and started to worship the new god. But the experiment was followed by an epidemic that Soga opponents attributed to the displeasure of the kami. Accordingly, Kinmei had the statues cast into the Naniwa Canal and the temple was burnt to the ground. The chronicle item concludes with the report that, on that day, winds blew and rain fell under a clear sky.

– The Gango-ji engi agrees that a presentation of Buddhist scrtiptures and statues was made by King Songmyong and that this episode was followed by a conflict between powerful families, among those the Soga clan supported the adoption; but says that it happened in 538, rather than in 552.

The scholars are more likely to follow this second theory, since the Gango-ji engi is considered a more objective source (while the Nihon Shoki is strongly influenced by the aim to glorify the Emperor) and because the other accounts display some inconsistencies (e.g. the envoyee from Paekche is not mentioned otherwise; and more remarkably the texts presented to Kinmei appeared to be inspired from a later translation).

The debate on the introduction of Buddhism was inspired not so much by spiritual concerns, but rather by power and personal interests. The main supporters of the new religion were the members of the Soga clan; they considered Buddhism a way to increase their influence since they had Korean heritage – Soga no Iname’s ancestors names Soga no Koma (蘇我 高麗) and Soga no Karako (蘇我 韓子) are references in Chinese characters to Koguryou and Gaya region respectively; moreover we can notice how, during Soga no Umako’s time of influence, the capital was temporarily transferred to Kudara Palace in Nara.

The opposition to Buddhism came from families such as the Mononobe, who unlike the Soga had ancient Japanese origins and were motivated by conservatorism and some kind of xenophobia, and the Nakatomi, who had a personal interest as well since they claimed descent from divine clan ancestors “only a degree less sublime than the imperial ancestors” and were High Priests of Shinto purification rites.

The conflict deveoped into a war between the mentioned clans.

In 584, a statue of Maitreya and other Buddhist images were sent from Korea to Soga no Umako, who restored the worship and built a new temple and had a girl ordained as a Buddhist nun. Again, an epidemic swept through Japan and the images were destroyed by Mononobe no Moriya.

The conflict ended only in 587, when Soga no Umako won military over his opponent at the battle of Kisuri.

The reason why he didn’t install himself as a new Emperor is speculated and the most accepted answer is that he was 1. part of an immigrant although powerful clan 2. the main sponsor of Buddhims, while the Emperor was strongly related to worship of native agricultural kami.

In Paekche, foreign kings had troubles governing the native Han population; Umako might have known this and preferred another policy.

Capitals of Japan – 3 – Heijou-kyou

March 14, 2011

With the beauty of green and vermilion,

The imperial city of Heijou is now in its glory,

Like the brilliance of flowers in full bloom.

Fujiwara-kyou soon appeared being still too small for the needs of the capital, so Empress Genmei, in 708, ordered the construction of a new city, indicating Heijō-kyō (平城京, present-day Nara) as a propitious location since it had been shown be sacred signs.

She was probably influenced by other considerations, such as the ancient custom of moving the capital at the beginning of a new reign. Moreover, an important role was given by the support of Fujiwara no Fuhito: more concerned with strategic and economic questions than with geomancy and divination, he probably understood quite well that Heijou was close to rivers by which goods could be transported easily, such as Kizu River (navigable all the way to Naniwa), that was six kilometers north of the new capital, and Saho River, flowing into the Yamato River that led to Inland Sea at Naniwa. Moreover, just as Fujiwara-kyou, Heijou-kyou had mountains on three sides, so that it was a strategically safe area.

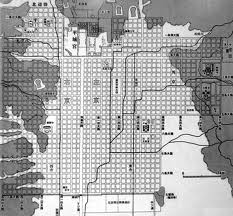

The capital was moved to Heijou-kyou in 710. It was modeled after Chang’an, the capital of Tang Dynasty China, although Heijou-kyou lacked walls. Like Fujiwara-kyou, it was built in a grid pattern; its surface was a rectangle of 4,3 x 4,8 km.

The main street, Suzaku, that led to the Palace and ended with the Suzaku-mon on the other side, had a width of 70m. The city was divided in two areas, separated by the street, and in nine lots in the north-south direction and in eight lots in the east-west one. A further group of 3×4 lots was added in the eastern part of the city. The overall form of the city was an irregular rectangle, and the area of city is more than 25 km2.

Recent archaeological investigations have noticed special geographical ties between Heijou and Fujiwara. Moving north from the avenue that ran along the western side of the old capital, one entered the Great Suzaku Avenue in the new one. And proceeding north from the street that ran along the eastern side of Fujiwara, one entered Heijou-kyou’s East Capital Avenue. The new city was therefore not only laid out in the square fashion of a Chinese capital but also had avenues that ran in preciselythe same direction as those of Fujiwara. The reasons of this geographical relationship are speculated and probably heve to do with the desire of the sovreign to be honored as a direct lineal descendant of predecessors who had reigned at Fujiwara.

Heijou-kyou flourished as Japan’s first international and political capital, with a population of around 200,000, where merchants of China, Korea, India were coming for their trades.

The Palace, located in the north end of the capital city, was built as usual according to Chinese criteria and covered an area of more than 1km2. It included the Daigoku-den, where governmental affairs were conducted, the Choudou-in where formal ceremonies were held, the Dairi, the Emperor’s residence, and offices of the administrative agencies.

The spiritual authority of the Emperor was enhanced also by the erection of beautiful Buddhist temples: soon after Empress Genmei moved her palace to Heijou-kyou, temples originally built in the Asuka area (especially the Asuka-dera, Yakushi-ji, Daian-ji, and Kofuku-ji) were rebuilt at the new city.

Heijou-kyou was the capital city of Japan during most of the Nara period, from 710-740 and again from 745-784.

It was abandoned from 740 to 745 by Emperor Shoumu, who restored the habit of changing location in order to fight the misfortune that appeared to be dogging the Country: after the drought and the following smallpox epidemic in 737, then the death at the age of 2 of the Imperial prince and the rebellion of Fujiwara Hirotsugu in the Kyushu, he moved the capital to Kuni-kyou, where he stayed from 740 to 744; but the city was not completed, as the capital was moved again to Naniwa and then to Shiragaki Palace in the Shiga prefecture. But eventually the practical needs of the central organization prevailed and Emperor Shoumu moved back to Heijou-kyou.

Special message (11th March 2011)

March 11, 2011

I was writing another post but after what happened today I just though I had to wish good luck to all our Japanese friends and condolences for the victims of the earthquake.

Wow, I notorioulsy suck at saying this kind of things but the intention was good.