The introduction of Buddhism in Japan

March 28, 2011

While I am not so much into the history of Buddhism generally speaking, I am intrigued by the facts surrounding its introduction in Japan.

There are two theories on how it was introduced. The first one is based on the famous Nihon Shoki (720), the other on an early history of Yamato’s first great temple entitled “Gangouji Garan Engi Narabi ni Ruki Shizaichou” (元興寺伽藍縁起并流記資財帳?, “Origins of the Gangouji Monastery and Its Assets”), also known as Gangouji Garan Engi, compiled by an unnamed Buddhist monk in 747.

– According to the Nihon Shoki accounts, Buddhism was introduced in Japan in 552, the thirteenth year of the Kinmei reign, when King Songmyong of Paekche sent to the Japanese Emperor an envoy bearing (together with a plea for military aid against Silla) a Sakyamuni idol, two Buddhist scriptures and and a message in which Songmyong recommended the adoption of Buddhism on the grounds that this religion had greatly benefited the rulers of other lands. Emperor Kimmei, says the Nihon Shoki, “leaped for joy”, but his ministers were less jubilant: while Soga no Iname was enthousiastic, Mononobe no Okoshi was reluctant, being concered to offend the native kami, on whose benevolence depended the abundance of the harvest and the health of the state

Since the ministers were divided on the issue of the adoption, Kinmei had Soga no Iname perform Buddhist rituals experimentally. Iname turned his house into a temple and started to worship the new god. But the experiment was followed by an epidemic that Soga opponents attributed to the displeasure of the kami. Accordingly, Kinmei had the statues cast into the Naniwa Canal and the temple was burnt to the ground. The chronicle item concludes with the report that, on that day, winds blew and rain fell under a clear sky.

– The Gango-ji engi agrees that a presentation of Buddhist scrtiptures and statues was made by King Songmyong and that this episode was followed by a conflict between powerful families, among those the Soga clan supported the adoption; but says that it happened in 538, rather than in 552.

The scholars are more likely to follow this second theory, since the Gango-ji engi is considered a more objective source (while the Nihon Shoki is strongly influenced by the aim to glorify the Emperor) and because the other accounts display some inconsistencies (e.g. the envoyee from Paekche is not mentioned otherwise; and more remarkably the texts presented to Kinmei appeared to be inspired from a later translation).

The debate on the introduction of Buddhism was inspired not so much by spiritual concerns, but rather by power and personal interests. The main supporters of the new religion were the members of the Soga clan; they considered Buddhism a way to increase their influence since they had Korean heritage – Soga no Iname’s ancestors names Soga no Koma (蘇我 高麗) and Soga no Karako (蘇我 韓子) are references in Chinese characters to Koguryou and Gaya region respectively; moreover we can notice how, during Soga no Umako’s time of influence, the capital was temporarily transferred to Kudara Palace in Nara.

The opposition to Buddhism came from families such as the Mononobe, who unlike the Soga had ancient Japanese origins and were motivated by conservatorism and some kind of xenophobia, and the Nakatomi, who had a personal interest as well since they claimed descent from divine clan ancestors “only a degree less sublime than the imperial ancestors” and were High Priests of Shinto purification rites.

The conflict deveoped into a war between the mentioned clans.

In 584, a statue of Maitreya and other Buddhist images were sent from Korea to Soga no Umako, who restored the worship and built a new temple and had a girl ordained as a Buddhist nun. Again, an epidemic swept through Japan and the images were destroyed by Mononobe no Moriya.

The conflict ended only in 587, when Soga no Umako won military over his opponent at the battle of Kisuri.

The reason why he didn’t install himself as a new Emperor is speculated and the most accepted answer is that he was 1. part of an immigrant although powerful clan 2. the main sponsor of Buddhims, while the Emperor was strongly related to worship of native agricultural kami.

In Paekche, foreign kings had troubles governing the native Han population; Umako might have known this and preferred another policy.

Shunbun no Hi – Vernal Equinox Day

March 24, 2011

I’ve just realized how late I am! Actually, this year’s Shunbun no Hi occurred on March 21, that is to say last Monday. 遅くなって、申し訳ありません。

Shunbun no Hi (春分の日) is a public holiday, that occurs on the date of the vernal equinox, which can be on March 20 or 21. Since astronomical measurements are needed, the date is not declared until February of the previous year.

The original celebration of Spring Equinox dates back to the eighth century and was known as Shunki Korei-sai (春季皇霊祭), a tradition related to Shinto: from 1878 to 1948, this was a day in which the Japanese worshipped the past Emperors.

After 1948, like other Japanese holidays, this holiday was repackaged as a non-religious public holiday for the sake of separation of religion and state in Japanese Constitution.

Nowadays it is a national holiday in Japan; it is considered a day to spend with nature and to express our affection for all living things. In the seven-day period surrounding the Vernal Equinox Day (彼岸 Higan), Japanese people pay respect to their ancestors, just like on New Year’s Day and Obon: they visit their family graves to clean them and offer flowers and incense. They also offer Higan dumplings called Ohagi and Botamochi (springtime treat made with sweet rice and sweet azuki) on thier household altars. These kinds of food have oval or round shapes since, according to the tradition, ancestors’ spirits prefer round food.

They say that after Vernal Equinox Day “the chill of winter finally disappears” and temperatures start to rise. Cherry blossoms, marking the beginning of spring in Japan, often begin to bloom around this time, starting from the southern parts of the country and gradually moving up north as temperatures increase.

Capitals of Japan – 3 – Heijou-kyou

March 14, 2011

With the beauty of green and vermilion,

The imperial city of Heijou is now in its glory,

Like the brilliance of flowers in full bloom.

Fujiwara-kyou soon appeared being still too small for the needs of the capital, so Empress Genmei, in 708, ordered the construction of a new city, indicating Heijō-kyō (平城京, present-day Nara) as a propitious location since it had been shown be sacred signs.

She was probably influenced by other considerations, such as the ancient custom of moving the capital at the beginning of a new reign. Moreover, an important role was given by the support of Fujiwara no Fuhito: more concerned with strategic and economic questions than with geomancy and divination, he probably understood quite well that Heijou was close to rivers by which goods could be transported easily, such as Kizu River (navigable all the way to Naniwa), that was six kilometers north of the new capital, and Saho River, flowing into the Yamato River that led to Inland Sea at Naniwa. Moreover, just as Fujiwara-kyou, Heijou-kyou had mountains on three sides, so that it was a strategically safe area.

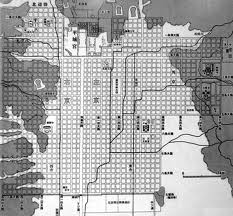

The capital was moved to Heijou-kyou in 710. It was modeled after Chang’an, the capital of Tang Dynasty China, although Heijou-kyou lacked walls. Like Fujiwara-kyou, it was built in a grid pattern; its surface was a rectangle of 4,3 x 4,8 km.

The main street, Suzaku, that led to the Palace and ended with the Suzaku-mon on the other side, had a width of 70m. The city was divided in two areas, separated by the street, and in nine lots in the north-south direction and in eight lots in the east-west one. A further group of 3×4 lots was added in the eastern part of the city. The overall form of the city was an irregular rectangle, and the area of city is more than 25 km2.

Recent archaeological investigations have noticed special geographical ties between Heijou and Fujiwara. Moving north from the avenue that ran along the western side of the old capital, one entered the Great Suzaku Avenue in the new one. And proceeding north from the street that ran along the eastern side of Fujiwara, one entered Heijou-kyou’s East Capital Avenue. The new city was therefore not only laid out in the square fashion of a Chinese capital but also had avenues that ran in preciselythe same direction as those of Fujiwara. The reasons of this geographical relationship are speculated and probably heve to do with the desire of the sovreign to be honored as a direct lineal descendant of predecessors who had reigned at Fujiwara.

Heijou-kyou flourished as Japan’s first international and political capital, with a population of around 200,000, where merchants of China, Korea, India were coming for their trades.

The Palace, located in the north end of the capital city, was built as usual according to Chinese criteria and covered an area of more than 1km2. It included the Daigoku-den, where governmental affairs were conducted, the Choudou-in where formal ceremonies were held, the Dairi, the Emperor’s residence, and offices of the administrative agencies.

The spiritual authority of the Emperor was enhanced also by the erection of beautiful Buddhist temples: soon after Empress Genmei moved her palace to Heijou-kyou, temples originally built in the Asuka area (especially the Asuka-dera, Yakushi-ji, Daian-ji, and Kofuku-ji) were rebuilt at the new city.

Heijou-kyou was the capital city of Japan during most of the Nara period, from 710-740 and again from 745-784.

It was abandoned from 740 to 745 by Emperor Shoumu, who restored the habit of changing location in order to fight the misfortune that appeared to be dogging the Country: after the drought and the following smallpox epidemic in 737, then the death at the age of 2 of the Imperial prince and the rebellion of Fujiwara Hirotsugu in the Kyushu, he moved the capital to Kuni-kyou, where he stayed from 740 to 744; but the city was not completed, as the capital was moved again to Naniwa and then to Shiragaki Palace in the Shiga prefecture. But eventually the practical needs of the central organization prevailed and Emperor Shoumu moved back to Heijou-kyou.

Special message (11th March 2011)

March 11, 2011

I was writing another post but after what happened today I just though I had to wish good luck to all our Japanese friends and condolences for the victims of the earthquake.

Wow, I notorioulsy suck at saying this kind of things but the intention was good.

Hinamatsuri

March 3, 2011

Since March 3rd is Hinamatsuri (Girl’s Day) in Japan, I am dedicating today’s post to this ceremony. Pretty obvious, I know, but anyway a good chance to learn something more on this tradition.

Hinamatsuri (雛祭, also known as hina-no-sekku, 雛の節句, or momo-no-sekku, 桃の節句, joshi-no-sekku, 上巳の節句) has its origin in an ancient Chinese custom in which people transferred thier misfortune to a doll and then floated it on a river in order to ward off evil spirits. In the middle of Heian period (794 – 1191) this custom was brought in Japan, 上司の節句, where it took the name of Hina-nagashi (雛流し, “floating dolls”). A fortune teller called onmyouji (陰陽師) used to pray and offer seasonal food to the Gods, then paper dolls were floated on a river or the see.

This is a Nagashibina set with a pair of paper dolls, a male and a female; however I've read that in Kitagi dolls are floated in groups of 13: 12 women and one man, the "sendo-san," to row the boat.

Hina-nagashi (or Nagashibina) is still celebrated in some sanctuaries, such as the Meiji Shrine and the Shimogamo Shrine near Kyouto, as a part of Girl’s Day; anyway, since fishermen complained about catching the dolls in their nets, they are now sent out on boats, and when the spectators are gone boats are taken back out of the water and burnt into a temple. Then habits are a little different in every area, for instance at Meiji Shrine dolls are rather made by fish-food so to be environmentally safe.

Anyway, the mos typical tradiction of Girl’s day is the display of a set of dolls, which comes from a combination of the practice described above and the Hina-asobi ( 雛遊び, “playing with dolls”) that was common among women and children in the Heian court, of which we find descriptions in Murasaki Shikibu’s “Genji monogatar” and Sei Shounagon’s “Makura no Soushi”.

From the combinations of these two customs stems the still practiced Hinamasturi, that was legally established as a national festival in 1687. The ceremony consists in the display of a set of ornamental dolls (雛人形, hina-ningyou) on a platform (雛壇, hinadan) covered with a red carpet. Few days before the festival, girls and their mothers take out the hina and arrange them on the red cloth. Peach blossoms are a typical decoration of the festival since they represent fertlity and positive feminine qualities such as grace and tranquillity.

Families offer to the altar also shirosake (white sake)

Families offer to the altar also shirosake (white sake)

and mochi, either flavored with a wild herb or colored

and cut into festive diamond shapes. after the festival

they are immediately taken down, since according to

the superstition leaving them there would result in a late

marriage of the daughter.

The hina ningyou set represents a royal wedding on a spring day at the imperial court of Heian and dolls have luxury clother that reproduce the style of that time. Dolls are not ordinary ones, nor old style paper dolls, but are made of a base material (generally wood), covered by gofun, a substance made principally of oyster shells and responsible for the dolls’ luster. Traditionally, the hair was either human hair, horsehair, or silk, although now there are many fibers used.

The altar is typically made of seven steps.

– On the top one, there is the Dairi-bina (内裏雛) or Dairi-sama, that is to say the Imperial couple. The two dolls are usually placed in front of a folding screen (屏風, byoubu), that is the most important decoration of the altar and may be plain, golden, or elaborately decorated. Optional are the two lampstands, called bonbori (雪洞), and the paper or silk lanterns that are known as hibukuro (火袋), are usually decorated with cherry or ume blossom patterns. The doll representing the Emperor has the richest clothing and a tall hat; the Empress has the traditional juunihitoe (十二単), that is to say a twelve-layered kimono. The traditional arrangement had the male on the right, while modern arrangements had him on the left (from the viewer’s perspective).

– The second tier displays three court ladies san-nin kanjo (三人官女), wearing scarlet pantaloons, each of them holding a sake equipment. Serving the dairi bina sake is part of the Shinto wedding ceremony, so th ey may be priestesses or miko.

ey may be priestesses or miko.

– The third tier holds five male musicians gonin bayashi (五人囃子).

– The fourth displays two Ministers: the Minister of the Right (右大臣, udaijin), depicted as a young person, and the Minister of the Left (左大臣, sadaijin), represented as much older. They are both armed, usually with bows and arrows, and occupy the far ends of their step. Between them there are covered bowl tables (掛盤膳, kakebanzen), and diamond-shaped stands (菱台, hishidai) bearing diamond-shaped ricecakes. Hishidai with feline-shaped legs are known as nekoashigata hishidai (猫足形菱台).

– The fifth tier, between the plants, holds three helpers or samurai as the protectors of the Emperor and Empress. They are the Maudlin drinker or nakijjougo (泣き上戸), the Cantankerous drinker or okorijougo (怒り上戸) and the Merry drinker or waraijougo (笑い上戸).

– On the sixth step there are items used within the palatial residence: a tansu (箪笥) a chest of drawers; a nagamochi (長持), a long chest for storing of kimono; two hasamibako (挟箱), small clothing boxes that together are a little shorter than the nagamochi and therefore are placed on top of it; a kyōdai (鏡台) a chest of drawers with a mirror on top; a haribako (針箱), that is to say a sewing box; two hibachi (火鉢), or braziers; and a daisu (台子, which is a set of utensils for the Japanese tea ceremony.

– On the seventh tire there are other items, that have to be outside the palace: a jubako (重箱), a set of nested laquered boxes for carrying food; a gokago (御駕籠 or 御駕篭), a palanquin; and a goshoguruma (御所車), an ox-drawn carriage favored by Heian nobility; less common is a hanaguruma (花車), an ox drawing a cart of flowers.

Then decorations are different in the various areas of Japan, according to local traditions: for instance, Kyouto-made altars have miniature kitchens and hearths for cooking, which you’ll never find in Toukyou ones.